This blog is about the first part of my internship which I did at the Intelligent and Autonomous Systems group at CWI, Amsterdam, under the supervision of Dr Hendrik Baier.

We wanted to find out a decent way to train neural networks using Evolution Strategies to play board games. Due to CoViD’19 I did my internship virtually, and I didn’t had access to CWI servers. Hence, we miniaturised the problem statement to solving a simple board game like Connect Four.

I was 16 when AlphaGo defeated 18 times world champion Lee Sedol. My Computer Science teacher told us this. At that time, I had no idea how big this achievement was. In my Sophomore year when I implemented DQN and found that DQN was struggling in CartPole environment, then I realised how difficult it is to train an agent for a complicated game like Go. I was very excited to explore in this field, and my internship gave me a chance.

Most of the work already done on Evolution Strategies (ES) are tested on domains like Atari 2600, maze and MuJoCo domain. To the best of my knowledge, none of the work in ES is done for the board games. Further, most of the work for board games only used

It is an open-source library managed and created by DeepMind. The library has several games and implemented algorithms. Unlike OpenAI Gym, Open Spiel has card games and board games. It also has some games which are now days used for benchmarking like Coin Run and Deep Sea.

Our experiments are limited only to Connect-Four. Because of the lack of computation power, we couldn’t do the experiments rigorously on other board games.

In ES a population of n individuals are formed, where each individual has a genotype. After each generation, the individuals are evaluated based on their performance (fitness). After evaluation, the individuals with lower fitness are killed and the individuals which are now left in the population produce offspring through crossovers or mutations. Specifically, in our work, we mutate individuals by adding some perturbations to the genotype. This process of evaluation, selection and mutation goes on until computation time runs out. Noticeable points in this process are 1) All individuals are independent of each other, which makes ES highly parallelisable; 2) we are taking net reward received by the individual as its fitness which solves the problem of temporal credit assignment; 3) also unlike policy-based methods, this technique is not prone to stick at suboptimal goal because of exploration caused by regular mutations; and finally 4) this algorithm does not require any backpropagation, which saves a lot of computation power and makes the whole process a lot faster.

Training neural network using ES is not something new. A lot of work has already been done in this field. Very recent work is done in Pourchot et al. [2019], which combined CEM with DDPG and TD3 algorithm and obtained some impressive results on MuJoCo domains like Swimmer. Some works have been done to see the trade-off between RL algorithms and ES like Such et al. [2018] and Salimans et al. [2017]. Both of these works compare RL algorithms and ES on Atari and MuJoCo simulator. Some useful findings of these works were:

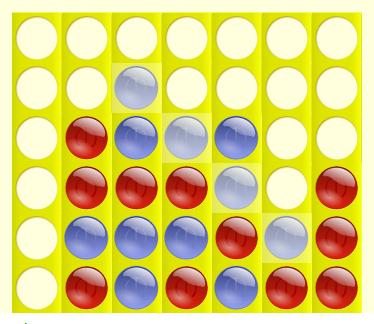

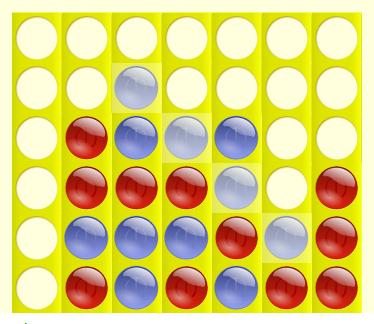

All the experiments done are for Connect-Four(aka 4 in a line) game. Connect Four is a two-player board game where players take turns dropping one coloured disc from the top into a seven-column, six-row vertically suspended grid. The pieces fall straight down, occupying the lowest available space within the column. The objective of the game is to be the first to form a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal line of four of one’s own discs. In our experiments, we used OpenSpiel for the simulation of Connect Four.

|  |

In the left game blue player won and red won the game in the right.

We started with Gaussian ES, it the most straightforward way to do mutations. However, adding small perturbations in the genome can change the behaviour of the agent entirely. Since we are using weights of NN as genotype, this problem of drastic mutation is more severe. This problem is not new, and researchers had come up with some techniques to resolve this issue. In our model to resolve this issue, we used Safe Mutations technique. Through this technique, the pipeline will make sure that the divergence between outputs from the childs’ network and parents’ network is less. To do so, they measure the gradient of the childs’ NN output. Read the Safe Mutation paper by Uber AI to understand the details.

Connect Four is a two-player game; hence, we need opponents against which an agent could play to measure its strength. We set tournaments for all individuals in the population against random agents. To deal with the stochasticity and to make fitness scores close to real value every tournament had a fixed number of matches, or you can say trials. So fitness is defined as the mean reward of the individual for all trials. Playing matches against a random agent can get an agent stuck in a local optimum because there are some trivial moves (like continuously dropping discs on the same column) which the agent can learn quickly and win a majority of matches. So agents must play matches against some more intelligent agents. One way to do this is by playing against agents from previous generations, we called them opponents, and this approach is called population play. The problem with this is that fitness doesn’t tell us how good our agent is compared to agents in previous generations because in each generation opponents are different. This issue can be resolved by measuring performance against random agents for comparisons (but not using it as fitness). Another problem with this method is, the population may overfit to the opponents, so we need to make sure that the population has enough diversity. To control overfitting, we keep testing the populations against all opponents we ever had. If the average fitness of the population crosses a threshold, then some (say 15%) of the opponents are replaced with individuals in the current population, and this goes on. We did most of the experiment on shallow architectures like a linear layer with 32 nodes.

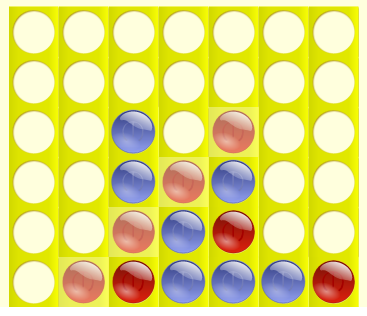

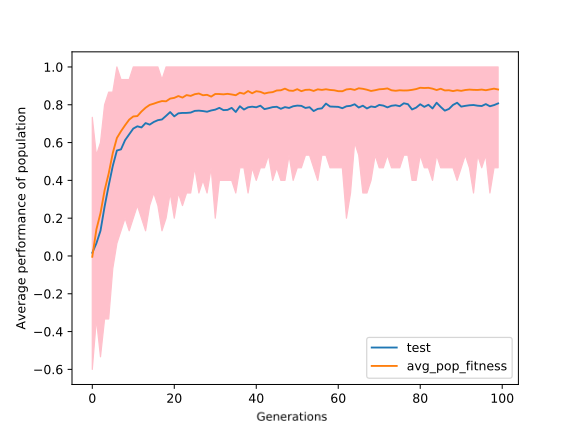

The purpose of these experiments was to figure out a half-decent way to play the board game connect four. We experimented with multiple algorithms like Gaussian ES, Gaussian ES with safe mutation and NS-GA. We tested these algorithms against random agents and opponents. In the initial experiment, we used a neural network with 6 hidden layers, and each hidden layer had 15 nodes. After running the experiment for 100 generations, we obtained the result shown in the figure below, which shows the average fitness of individuals in the population when tournaments are played against random agents. The pink region shows the deviation of fitness in the population. After every generation, testing is done, the results obtained in the testing are not used for measuring fitness.

The noticeable thing in the figure above is the gap between test and average population fitness. This might be because of biased fitness scores. Some individuals get lucky while playing the tournaments, they get good fitness scores, and their genotype is passed on to the next generation.

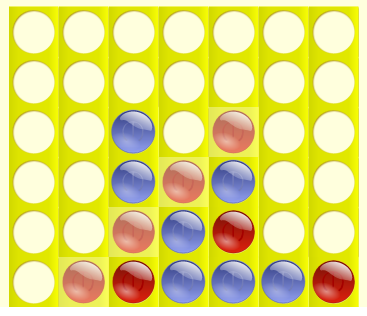

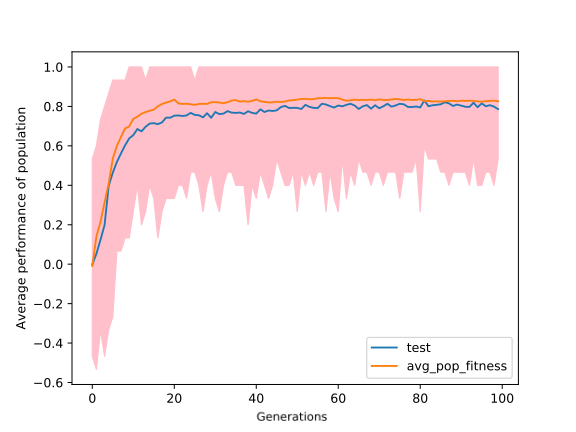

To avoid this situation, we kept doubling the number of trials in each tournament after every 20 generations. The result was as expected. The gap between test score and average fitness reduced significantly. See the figure in the right.

|  |

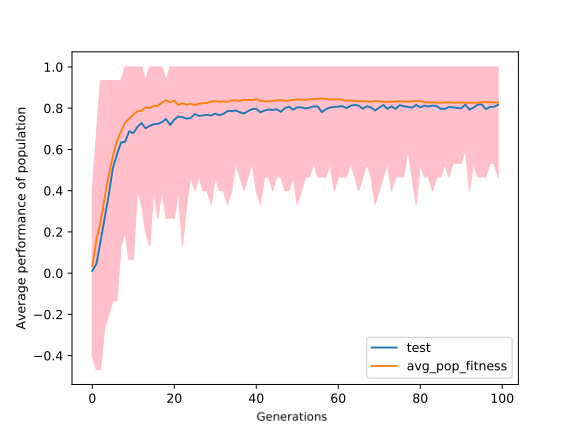

It was clear from the previous observations that after the 20th generation, there is no significant increase in average fitness. One of the possible reasons behind this could be large perturbations, due to which model jumps over the optimal solution. To check this, we kept decreasing the mutation magnitude geometrically by the factor of 0.90 after every 20 generations, look at the figure in the left. The left figure is very similar to the right one, which means that our approach did not work. By looking at the gameplay, we find out that agents had developed a hack by only dropping coins at the same column. Through this trivial strategy, they were able to win 90% of the matches. So we need to replace the random agent with something more intelligent. One way to do this is by playing against agents from previous generations; we call them opponents. Whenever the average fitness of the individuals in the population crossed a threshold(for our experiment we choose 0.80), then some members(we used 20%) of opponents are replaced with individuals in the population, and this goes on. The problem with this is that fitness does not tell us how good our agent is compared to agents in previous generations in absolute terms. This can be resolved by measuring performance against random agents see the figure below.

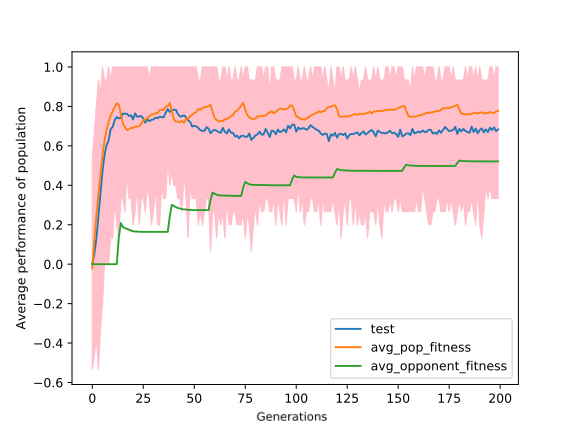

The problem with this method is, the population may overfit over the opponents. The figure is also evidence of this theory as the test score keeps dropping.

A similar strategy of making the agent play against themselves has been successfully imposed in many recent successful AI such as AlphaGo zero. But here the agents don’t play against themselves. They play against a team of opponents which is much more intelligent than random agents and eventually with every generation passes the opponents keep becoming more intelligent.

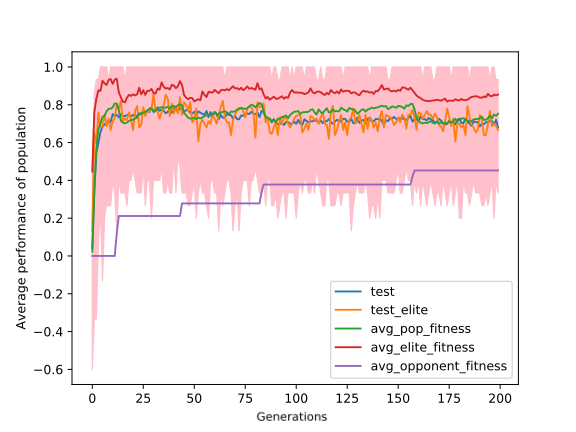

To understand this problem of overfitting more precisely we saw some tournaments, where we observe that the game strategy of all the agents are similar, like in the opening strategy which moves they play is fixed (like all agents will only make moves on the left side on the board). The most reasonable reason behind this could be that the opponents are similar due to which individuals find some hack to defeat the opponents. Opponents play a crucial role in the learning process of the population. We want our population to be trained against a diverse set of opponents for the sake of better generalisation. Earlier, we were adding some good individuals from the population to the opponents’ team. This way was not ensuring the diversity of opponents. So we took some inspiration from Novelty Search GA, and we made a novelty vector. A novelty vector is a list of actions taken by the agent in a definite set of states. We called it state-archive. Now, we use these novelty vectors to make clusters, using some clustering algorithm. In our experiments, we used K-Means and made 5 clusters. We pick an agent from each cluster and then add them to the opponents’ team. We keep sampling some states from the matches and add them to the state archive. After every three generations, we update the novelty vectors and then train the clustering model with the new set of novelty vectors. The results obtained from this were significantly different from the previous experiments, see the figure below. Now the gap between test score and fitness score is reduced. It means that the problem of overfitting is solved to some extent.

We have shown that it is possible to train neural networks on board games using ES. We had our computation limitations that’s why we only did the training till 200 generations on Connect Four domain. In future, we will try to do multi-processing to make it faster. Unlike RL algorithms, ES speed increases linearly with the number of processes. Which means they are a lot more efficient than RL algorithms. To make the opponents more diverse, we used the K-Means algorithm to create clusters of individuals in the population. The K-Means model takes novelty vectors as input. In our experiments, we used actions as novelty vectors. In future, we will try to use the weights of the neural network as novelty vectors. Note that if we use weights, then we can’t use Euclidean distance as distance metric in K-Means. We need to define our own distance metric or use some deep learning technique for the clustering.